Delia did everything right. She went to college, she got a teaching degree, she found a reliable job, and she got married. She and her husband had two kids. “We followed the traditional path to middle class and economic security,” she told me. “Or so I thought.”

As a teacher in New Jersey, Delia, age 41, makes around $115,000 a year; her husband, who works as a carpenter, makes $45,000. Their $160,000 combined family salary places them firmly in the American middle class, the boundaries of which are considered to be two-thirds of the US median household income on the lowest end and double that same median on the highest, and adjusted for location. (According to the Pew Middle Class Calculator, Delia’s household income places her family in the “middle tier” along with 49 percent of households in the greater tri-state area.)

To most people, $160,000 sounds like a lot of money. “Middle tier” sounds pretty solid. So why does Delia feel so desperate? She’s able to put $150 a month into a retirement account, but the family’s emergency savings account hovers at just $400. Going on vacation has meant juggling costs on several credit cards. “I don’t feel like I’ll ever have a day that I won’t be worried about money,” she said. “I’m resentful of my partner for not making more money, but more resentful of his crappy employer for not paying him more.”

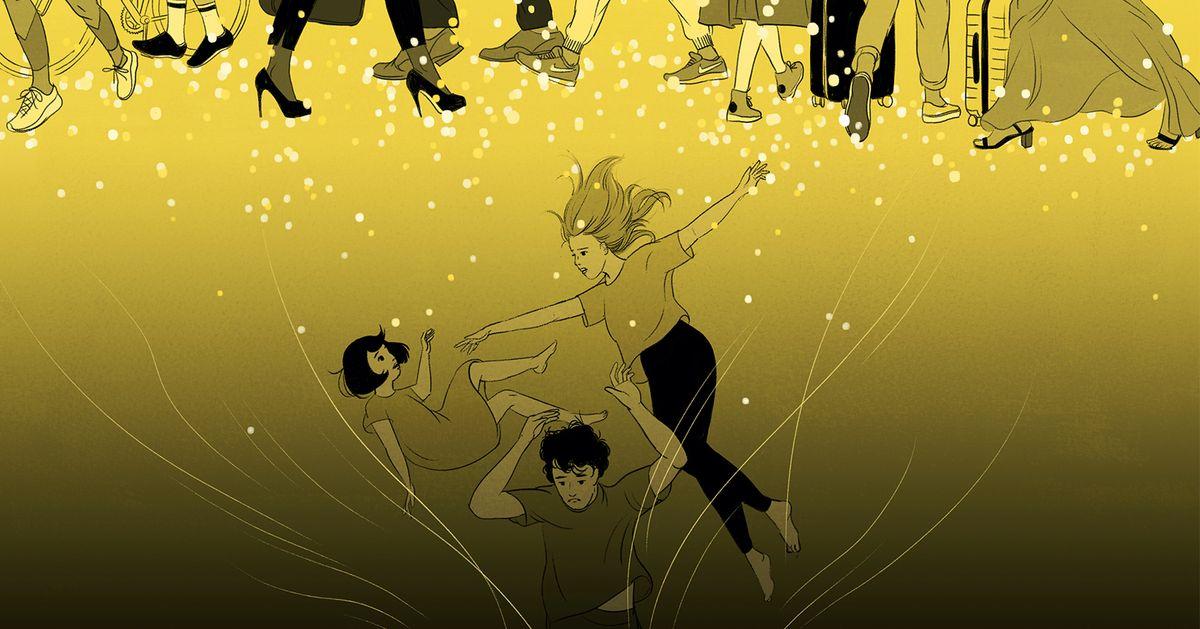

Delia is part of an expanding group of people whose income technically places them within the middle class of American earners but whose expenses — whether for housing, medical costs, debt payments, child care, elder care, or the dozens of other expectations that attend supposed middle-class living — leave them living month to month, with little savings for emergencies or retirement.

Pre-pandemic, middle-class Americans modeled the belief that everything was fine. Unemployment was low; consumer confidence was high; the housing market had “recovered.” In 2019, 95 percent of people in households making over $100,000 a year reported they were “doing okay” financially, a 13 percent increase from 2013. But those positive economic indicators obscured a larger reality.

Forty years ago, the term “middle class” referred to Americans who had successfully obtained a version of the American dream: a steady income from one or two earners, a home, and security for the future. It meant the ability to save and acquire assets. Now, it mostly means the ability to put your bills on autopay and service debt. The stability that once characterized the middle class, that made it such a coveted and aspirational echelon of American existence, has been hollowed out.

It’s difficult to tell if someone’s part of the hollow middle class because they’re still performing all the external markers of middle-classness. Before the pandemic, they were (and largely still are, absent a layoff) buying and leasing cars, purchasing homes, going on vacation, covering their kids’ education and activities. They’re just taking on massive loads of debt to do so.

As journalist and social critic Barbara Ehrenreich has pointed out, it’s very expensive to be poor. It’s also increasingly expensive to be middle class, in part because wages for all but the wealthy have remained stagnant for the past four decades. Most middle-class Americans seem to be making more — getting raises, however small, sometimes billed as “cost of living” increases. Yet these increases largely just keep pace with inflation, not the actual cost of living.

Basic costs are taking up bigger chunks of the monthly middle-class paycheck. In 2019, the middle class was spending about $4,900 a year on out-of-pocket health care costs. More middle- and high-income people than ever are renting, and 27 percent are considered “cost burdened,” paying more than 30 percent of their income on rent, particularly in expensive metro areas. Then there’s the truly astronomical price of child care. In Washington state, for example, which ranks ninth in the US for child care costs, care for an infant and a 4-year-old averages $25,605 a year, or 35.5 percent of the median family income; you can find costs in your state here.

Many middle-class households try to figure out what expenses they have to cover immediately with cash and what can be put on a credit card, financed, or delayed in some fashion. In March 2020, household debt hit $14.3 trillion — the highest it’s been since the 2008 financial crisis, when it reached $12.7 trillion. In the first quarter of 2020, the average loan for a new car was a record-breaking $33,738, with an average monthly payment of $569 (the average payment for a used car is $397).

And then there’s student loan debt, which, for Americans, currently totals $1.56 trillion. Not everyone has student loan debt, but among those who do — many with degrees and jobs that seemingly place them in the middle class — the average debt load is $32,731. The average monthly (pre-pandemic) payment is $393.

Some of these costs have shifted slightly since the beginning of the pandemic; federal student loan payments, for example, have been paused since February. But in January, just under 12 million renters will owe an average of $5,850 of back rent and utilities. And some costs, like child care, are poised to escalate even more once the pandemic is over.

So why don’t middle-class people just curb their spending? At the heart of this question is the heavy, confounding issue of American middle-class identity and the psychological and social wreckage that comes with losing it. “I don’t know that I could shake this identity regardless of how much money I do or don’t have,” Leigh, who makes $80,000 a year and spends all her take-home pay on rent and credit card bills, told me. “It’s ingrained within me.” If you’ve grown up poor and become middle class, there’s great bitterness in rescinding that status; if your parents worked years to enter the middle class, falling from it is often accompanied by great shame.

There’s also the difficulty of significantly shifting your family’s consumption patterns. Once set, many find it impossible to change their own expectations for vacations, activities, and schooling — let alone those of their partners or children. Why? Because the middle class is spectacularly bad at talking honestly about money. Readily available credit facilitates our worst habits, our most convenient lies, our most cowardly selves.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22167848/Hollow_middle_class___credit_card_spot.jpg)

Some say Americans writ large are bad at talking about money, but truly rich people talk about money all the time, as do truly poor people. Kids who grow up poor learn the refrain “we can’t afford it” at an early age; as Aja Romano pointed out in this Vox discussion of all that Hillbilly Elegy gets wrong, “when you’re poor, you know every cent you have in the bank, down to the last penny, and you have already calculated exactly how much gas you can put in your car and how far that gas will get you before you get out of money.”

It’s middle-class people, or people who still cling to middle-class identity even if they’ve risen above it or fallen out of it, who don’t know how to talk about money. They don’t know how to talk about it with their peers or their parents or their children, and oftentimes not even with their partners. Instead, so many of us allow ourselves to default to the vast middle, the typical, the median, the democratic “we” that shows up in television commercials — a place in the American imaginary that’s venerated by politicians and overwritten with narratives of bootstrapping, hard work, and meritocracy.

In truth, the American middle class has become less of an economic classification and more of a mode: a way of feeling, a posture toward the rest of the world, predicated on privilege of place. Which is why it’s so untoward to talk about the economic realities; the rising panic over medical bills exists on a different plane than the ineffable feeling of “normal.”

Normal is defined less by what it is than by what it is not. Put differently, no matter how precarious your middle-class existence might be, it feels essential to distance from or disidentify with the precarity of the poor or working class. You maintain your middle-class identity by defining yourself as not poor, not working class, regardless of your debt load or the ease with which you could descend into financial ruin. So many are so obsessed with defining themselves as not poor that they can’t grapple with the changes in spending habits that would actually prevent them from becoming so.

Solidarity — especially solidarity across classes — has been declining for decades. When the middle class first began to expand in the United States in the mid-20th century, it did so in large part through the work of unions, which advocated for salaries and benefits that allowed millions of workers to afford a down payment and save for the future. There are still hundreds of thousands of union workers in the middle class (teachers, nurses, tradespeople), but much of the solidarity with workers outside your profession, or even your specific workplace, has evaporated.

What’s more, most politicians have done a spectacularly poor job of framing policy that speaks frankly about class realities. They talk vaguely about expanding the middle class, and single out specific high costs like medical premiums, but when was the last time you heard a politician talk about credit card debt? The less these kinds of problems are talked about, the more individual they feel, as opposed to a reality for millions of Americans.

Delia, for example, is a real person, but Delia’s not her real name; she doesn’t want others knowing her family’s business. She also thinks all her friends and neighbors are in a better financial situation than she is. They don’t ever talk about it, but she thinks they have better rates on their mortgages, more equity in their homes — how else could they drive $60,000 SUVs and put pools in over the summer? But someone on the outside might look at Delia’s life and think something very similar.

That’s how you get the hollow middle: when a bunch of people are terrified of being poor, have no idea how to talk with others about money, and have no political will to advocate for changes that would alter their position.

When I first attempted to describe the condition of much of the middle class today — moderately high income, but with bills and debt that make it difficult to weave a safety net for their families — I wanted a word for it, an evocative term. The term “hollow middle” eventually came, via Twitter, from Carina Wytiaz, but the vast majority of people who responded said that what I was explaining was just, well, being middle class. Tons of debt, tons of bills, very little leftover.

However, the middle class only really started to hollow out over the past 20 years. Back in 1960, the personal savings rate (the percentage of income households were saving after taxes) was 11 percent. In 1990, it was 8.8 percent. By 2000, it had dropped to 4.2 percent, before eventually hitting a nadir of 3.6 percent in 2007. That number grew in the aftermath of the Great Recession, peaking at 12 percent in 2012 before falling again as consumers gained more “confidence” in spending. This is because consumer confidence doesn’t mean more savings; it means more people with access to credit are confident about using it, and low interest rates disincentivize savings.

We’ve been normalizing low savings rates at the same time that we’ve become more and more comfortable taking on consumer debt — a symptom, as financial analyst Karen Petrou put it, of “deep economic malaise.” In the early ’80s, the income-to-debt ratio hovered between 0.55 and 0.65, which meant that a household’s overall debt level amounted to between 55 percent and 65 percent of their income after taxes.

The ratio first hit 1.0 in 2003, and rose all the way to 1.24 before the 2007 crash. Now it’s stabilized at just under 1, so a middle-class family making $80,000 has somewhere around $80,000 in debt. Until relatively recently, the majority of that debt would have been mortgage debt. Over the past decade, the proportion has begun to shift toward student loans, auto loans, credit card debt, and medical debt: so-called “bad” debt.

More people are retiring with debt, too — or unable to retire, or coming out of retirement to service debt. In 2016, the median debt for a household headed by someone 65 or older was $31,300, more than four and a half times what it was in 1989. These debts come from mortgages, but also student loans taken out for their children or for themselves when they went back to school, mid-career, during one of the recessions of the 2000s, or credit card debt trying to cover costs when they were out of work.

“The jobs came back after the recession of 2001,” economist Christian Weller, whose research focuses on middle-class savings and retirement, told me. “But the wages never really grew. Benefits were cut, and then people were hit with yet another massive recession in late 2007, and job growth doesn’t really come back until 2010. That’s a long period of a lot of economic pain for a lot of people.”

When the jobs did come back, a lot of them weren’t great. People became employed as gig workers or independent contractors, precarious roles with few benefits and little stability. Those who had gone into debt to get through the Great Recession were now accumulating more debt in order to stay middle class, or to try and provide a middle-class future for their children. More than a decade later, only the top 20 percent of earners have actually recovered from the Great Recession, in part because the percentage of the middle class with appreciating assets — whether in the form of a home or stocks — has continued to decline.

Here, Delia’s story is instructive. Back in 2005, she had her teacher’s job, and her husband had a promising construction company. They were on solid economic footing for the first time and decided to do what a lot of people in that position do: buy a house. The problem with their strategy revealed itself only in hindsight; they bought at the height of the mid-2000s housing bubble. They hung on to their house as long as they could, but by 2012, they were drowning. They ended up shutting down her husband’s business and short-selling the house, leaving them with no equity.

Their home hadn’t been foreclosed on and their credit was still intact, but they suddenly felt seven years behind. They moved in with Delia’s parents, only to discover that they, too, had for years been struggling to pay their mortgage and had taken a bad modification in order to stay in their house. Delia and her husband started covering the mortgage payment, which is now $3,300 a month, and most monthly costs. Eight years later, they’re still there.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22169602/Hollow_middle_class___piggyback_spot.jpg)

Though Delia’s teaching job is steady, her husband is making less than he did when he ran his own company. They’re also paying private school tuition for their two daughters, which takes up a “huge chunk” of their income. They could pull their kids from private school and put them in public, but the kids have made their friends, and Delia’s intent on giving them the opportunity to get out of the same claustrophobic town where she grew up.

“If the girls want to come back and live here, that’s fine,” Delia explained. “But I want them to be able to write their own story and invent themselves as they see fit. Private school might give them access to better colleges, by which I mean better job opportunities or travel opportunities or meeting-different-people opportunities.”

One irony of the hollow middle is that attempts to secure your children’s class stability often reproduce debt patterns for the next generation. Delia’s middle-class in-laws are living in a paid-off house in Texas, but Delia’s parents, in her words, “have never made a good financial decision.”

That’s how they found themselves years behind on their mortgage, and that’s why Delia and her husband have been forced to take it on. Her parents have no savings, and Delia and her husband will continue to provide and pay for care for them as they age. If nothing about their financial situation or America’s exorbitant higher education costs changes over the next decade, either Delia and her husband or their children will likely take on large amounts of student debt to pay for college.

For the top earners in our society, wealth and assets reproduce wealth and assets. For the hollow middle class, debt reproduces debt. The major difference between the ostensibly middle class and the poor is that one group began life with access to credit and had just enough support and funds to keep accessing it.

Over the months to come, I’ll be focusing on different aspects of the hollow middle class for this column: people who’ve been unable to uphold the performance of middle-class status in the shadow of Covid-19; whose education places them in the “cultural” middle class but whose wages place them barely above the poverty line; whose parents immigrated to the US to obtain and pass down middle-class stability but now struggle to sustain what they worked so hard to provide.

I’ll be talking to those who feel ambivalent about, shut out from, or trapped in homeownership; those who are struggling to pay for elder care and child care at the same time; and others who are now supporting members of their extended family after reaching the middle class. There are so many intersecting and complicated ways to be part of the hollow middle today, and I want to go deep into the economic shifts, governmental policies, and lived experiences that inform them.

The suffering of the housed, the fed, and the employed is not to be equated with the suffering of those facing eviction, hunger, and chronic unemployment. But if the middle class is the backbone of America, what does it communicate about the state of the nation — psychologically, politically, sociologically — that the backbone is too weak to support its own weight? If savings are shorthand for promise and potential, what does it mean that we have so little of it? At what point do we abandon the farce of the stable, secure American middle class and start talking about ways to make life more secure for everyone, up and down the actual income scale?

The more we insist on obscuring the economic realities of middle-class existence, the harder it is to muster the political and social might to actually confront income inequality. We continue to think of our struggles as personal, and shameful, and our responsibility alone, instead of as symptoms of systemic failure, the result of broken ideals of the past jury-rigged to the present.

“The walls are closing in,” Nicole, who lives in South Carolina on $65,000 a year with no savings and no support system, told me. “The chasm between income and expenses just grows. I don’t know where the system will break. But it will, if we don’t do something about it.”

If you’d like to share your experience as part of the hollow middle class with The Goods, email [email protected] or fill out this form.

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: www.vox.com