Among the Padma Shri awardees chosen this year are two Dalit artists from Bihar, Ramchandra Manjhi, a ‘naach’ performer, and Dulari Devi, a Mithila painter.

To reach Manjhi and Dulari, the national honour has travelled a long way, down dirt roads and mud tracks, to their houses in caste-divided, poverty-stricken Bihar villages. And both the new Padma Shris say it is their life circumstances that give their art the vitality that makes it shine bright, winning alike the hearts of their villagers and national awards.

Ramchandra Manji –– ‘Refinement at the cost of popular connect is stupid’

For 84 years now, Ramchandra Manjhi has been a ‘launda naach’ artiste, dressing up as a woman to perform the songs and plays of Bhikhari Thakur (December 8, 1887- July 10, 1971), the ‘Shakespeare of Bihar’. Born in village Tujarpur in Saran district –– where he still lives –– Manjhi was 10 when he started performing, and soon came in touch with Thakur, whose troupe would visit a nearby village for practice. He hasn’t left the stage since.

“Bhojpuri never saw a writer like Bhikhari Thakur again, and through our performances, we are keeping him alive. The central theme of his works was what migration for work does to a society. Often, when we are written about, the focus is more on us dressing up as women than on our work, but it is our content that has kept us relevant and popular all these decades,” Manjhi tells The Indian Express over the phone.

In his 80 years on stage, Manjhi says he has toured various cities of India, performed in government-sponsored cultural spaces to stages paid for by upper caste landlords, attracted cheers and jeers, but made sure his art stayed democratic.

“I was always clear that my first duty was to the village audience that can’t access or enjoy the more effete forms of entertainment. Our ticket prices have not gone up beyond a point, if a show is scheduled at a village and a richer man offers more money on the same day, I refuse. We travel hundreds of kilometres, going village to village, but we often choose to walk than make our poorer patrons pay for travel costs,” says the 94-year-old artiste.

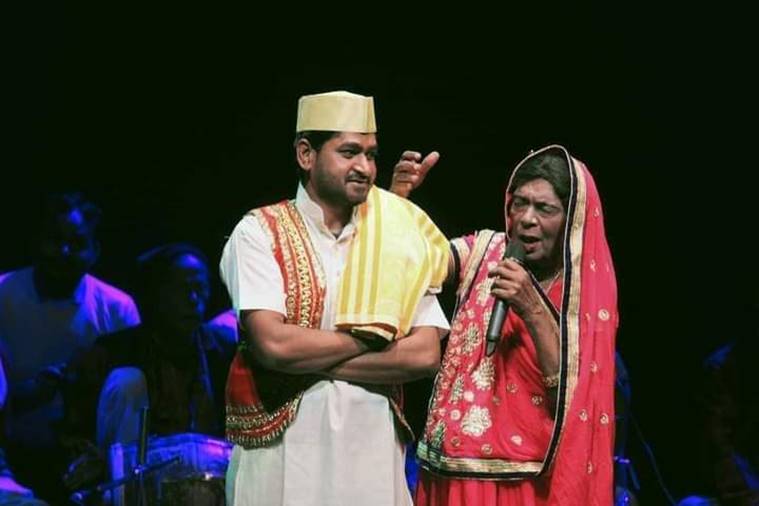

Dost (left) and Manjhi on stage. (Photo courtesy: Naresh Gautam/Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training & Research Centre)

Dost (left) and Manjhi on stage. (Photo courtesy: Naresh Gautam/Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training & Research Centre)

Helping Manjhi with the conference call is Dr Jainendra Dost, a JNU scholar who now runs the Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training & Research Centre in Chhapra. Dost says Manjhi’s life on stage has involved battling economic odds, caste discrimination, taunts for dressing up as a woman, but he has kept at it, powered by the need for public self-expression of a community historically denied that privilege.

“Thakur belonged to the low nai (barber) caste. He wrote about the subaltern among the subaltern –– the able-bodied lower caste man left to cities for work, leaving behind broken, vulnerable families, something very much happening in today’s Bihar too. He was the first to bring their stories to stage. That Bhojpuri never produced another Bhikhari Thakur shows the hold upper castes continue to have on art, and that’s one reason why Manjhi and his troupe, all elderly men now, hold on to the stage –– if they leave, who tells their stories?” Dost says.

Even today, says Dost, the way naach is consumed by upper and lower castes in villages is different –– the upper castes are watching hired artistes, the lower castes are watching their own people bring their stories alive. “When Thakur started writing, his audience could not afford the baijis (courtesans) the upper castes patronised. So men performed women’s parts too. But upper castes called it launda naach, a derogatory term that has stuck, forming a negative perception about the art form,” he adds. “Till a few years ago, when Ramchandra ji would perform at stages paid for by upper castes, men would poke their stomachs with bhalas (long, pointed weapon), currency notes stuck on the tip. They are often taunted with vulgar slurs over dressing up as women.”

Manjhi is more peaceable about it. “Well, I do wear saaris and make-up, so why should I mind if I am called effeminate? Over the years, we have learnt how to deal with these things –– we know when to diffuse a situation with a smile, or when to turn stern.”

The quest to keep his art accessible has meant Manjhi is still far from a rich man –– with his Padma Shri winnings, he hopes to build a toilet at his house. Does he think the award will get his art more recognition?

Now 94, Manjhi has been on stage since he was 10 years old. (Photo courtesy: Naresh Gautam/Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training & Research Centre)

Now 94, Manjhi has been on stage since he was 10 years old. (Photo courtesy: Naresh Gautam/Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training & Research Centre)

“The Padma Shri will hopefully mean more people outside Bihar hear of us, but we have never lacked recognition. Recognition is not 50-100 “sophisticated” people knowing your name, it is the love you get on stage,” Manjhi is firm. “I have learnt Kathak, I can sing several classical ragas. But that is not what my audience connects with. I intend to give my audience quality content they can enjoy. So-called refinement and respectability, at the cost of mass connect, is just stupid.”

Dulari Devi –– ‘Painting brought me the colours my life lacked’

Dulari Devi, 53, lives in village Ranti, in Madhubani district. She first picked up the paintbrush when working as a domestic help at the house of a Mithila painter. In the almost three decades since, she has used it to bring new colours to her and her family’s life, add beauty to the world, and also make more prominent the ‘Dalit school’ in an art still associated strongly with Maithil Brahmins.

“I grew up in immense poverty, never went to school. We belong to the Mallah (fishermen) caste, so my father would catch fish and my mother worked as a field labourer. I was married off at 13, but after my six-month-old daughter died, I came back home, and started working as a house help for Mahasundari Devi, who made Mithila paintings. She noticed my interest in the art, and a few years later, when the government offered a small training course on Madhubani paintings, helped me pursue it. At Mahasundari Devi’s place, I came in contact with the great Mithila painter Karpoori Devi, who became my mentor, my second mother,” says Dulari.

Dulari Devi says she loves filling her paintings with bright colours, ‘as my life lacked colours for a long time’. (Photo: Express)

Dulari Devi says she loves filling her paintings with bright colours, ‘as my life lacked colours for a long time’. (Photo: Express)

Did she always have an interest in art? “Growing up, I was so busy battling poverty and just surviving that I didn’t even think of art,” Dulari Devi smiles. “But things would catch my attention, you know, I would get lost staring at a tree, I could watch children playing for hours, I specially loved watching people dressed in pretty clothes, because I never had any. Now, people tell me I have great observation skills and I pay attention to detail. But I never thought of it like that, I just draw what I see or what I can imagine,” she says.

Dulari Devi has travelled to various cities in India on government painting contracts, teaches Madhubani painting to children, has had books written on her. How does it feel to have achieved so much? “I honestly don’t get a lot of this. Teaching makes me happy. I live with my brother and recently, during the lockdown, his paan shop didn’t have much business. That time, it was my earnings from painting a nearby school wall that kept us going. That felt nice,” she says.

This fact, that art for Dulari Devi is as much livelihood as labour of love, brings her paintings pulsatingly alive, says Sunil Kumar, a former journalist from Bihar who has long been associated with her, and runs Folkartopedia, a digital archive of India’s traditional art forms.

“For Dulari Devi, art is not an abstract pursuit. She paints to earn a living, and she paints what she sees around her. Despite no conscious attempt to be political, her paintings have caste and political commentary running through them. To give just one example, she once painted a flood rescue operation scene, in which the richer, upper caste people are being rowed away to safety first, and a lower caste woman is watching, waiting for her turn to be saved, even though boatmen are traditionally people from her own community,” says Kumar.

Dulari Devi is proficient in both the ‘Kachnhi ‘and ‘Bharni’ forms of Mithila art –– the former being mainly sketches, and the latter involving filling the sketches with colours –– but enjoys Bharni more. “I love colours,” she says. “My early life was so dark and desolate that I love filling up my drawings with colours.”

A wall of Dulari Devi’s home painted by her nephew Rajesh Mukhiya, whom she is teaching her art to. (Express photo: Ashish Kumar Jha)

A wall of Dulari Devi’s home painted by her nephew Rajesh Mukhiya, whom she is teaching her art to. (Express photo: Ashish Kumar Jha)

Within Madhubani painting, there are different strains –– art as practised by upper castes and lower castes. “Kachni, for example, is practised more by upper castes,” Kumar explains. “The choice of motifs is different, upper castes have more cosmic subjects, drawing Ganesha, raas leela, scenes from the Ramayana. Lower castes draw the life they see around them. Dulari Devi is brilliant in whatever she draws, and her immense skill has brought such recognition to her art that the limelight is falling on her ‘slice of lower caste life’ pieces too,” Kumar adds.

What does the Padma Shri mean to her? “To be honest, I realised what a massive deal it was only when I saw how excited and overjoyed my students were,” Dulari Devi says.

“She is the pride of the village,” pipes up her nephew Rajesh Mukhiya, one of her students. “Who would have ever thought a mallah’s illiterate daughter would bring such honour and recognition to the village?”

“I don’t know about all that,” says Dulari Devi. “All I can say is after the bad cards dealt me early in life, art has redeemed me, the way Lord Ram redeemed Ahilya.”

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: indianexpress.com