But because the researchers couldn’t collect specimens, they can’t yet say what exactly these sponges and other critters could be eating. Some sponges filter organic detritus from the water, whereas others are carnivorous, feasting on tiny animals. “That would be sort of your headline of the year,” says Christopher Mah, a marine biologist at the Smithsonian, who wasn’t involved in the research. “Killer Sponges, Living in the Dark, Cold Recesses of Antarctica, Where No Life Can Survive.”

And Griffiths and his team also can’t yet say if mobile creatures like fish and crustaceans also live around the rock—the camera didn’t glimpse any—so it’s not clear if the sessile animals face some kind of predation. “Are they all eating the same food source?” asks Griffiths. “Or are some of them kind of getting nutrients from each other? Or are there more mobile animals around somehow providing food for this community?” These are all questions only another expedition can answer.

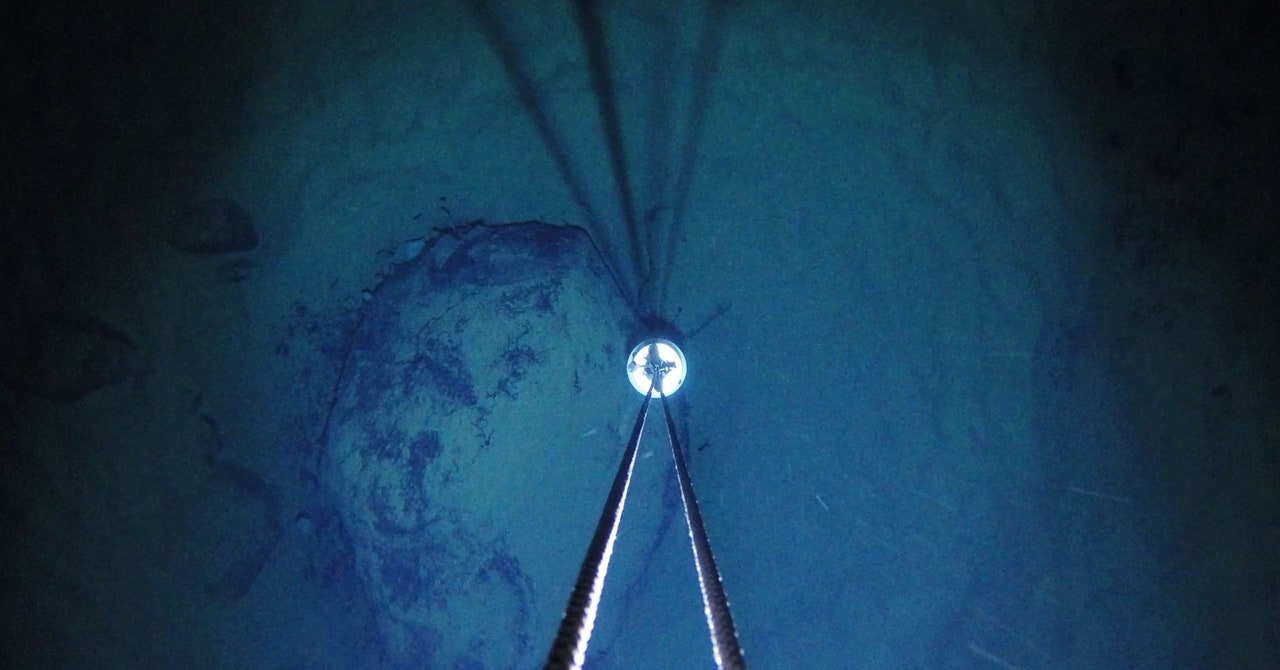

It does appear that sedimentation around the rock isn’t very heavy, meaning the animals aren’t in danger of being buried. “It’s kind of a Goldilocks-type thing going on,” says Griffiths of the rock’s apparently fortuitous location, “where it’s got just enough food coming in, and it’s got nothing that wants to eat them—as far as we can tell—and it’s not getting buried by too much sediment.” (In the sediment surrounding the rock, the researchers also noticed ripples that are typically formed by currents, thus bolstering the theory that food is being carried here from afar.)

It’s also not clear how these stationary animals got there in the first place. “Was it something very local, where they kind of hopped from local boulder to local boulder?” asks Griffiths. Alternatively, perhaps their parents lived on a rock hundreds of miles away—where the ice shelf ends and more typical marine ecosystems begin—and released their sperm and eggs to travel in the currents.

Because Griffiths and his colleagues don’t have specimens, they also can’t say how old these animals are. Antarctic sponges have been known to live for thousands of years, so it’s possible that this is a truly ancient ecosystem. Perhaps the rock was seeded with life long ago, but currents have also refreshed it with additional life over the millennia.

The researchers also can’t say whether this rock is an aberration, or if such ecosystems are actually common under the ice. Maybe the geologists didn’t just get extremely lucky when they dropped their camera onto the rock—maybe these animal communities are a regular feature of the seafloor beneath Antarctica’s ice shelves. There’d certainly be a lot of room for such ecosystems: These floating ice shelves stretch for 560,000 square miles. Yet, through previous boreholes, scientists have only explored an area underneath them equal to the size of a tennis court. So it may well be that they’re out there in numbers, and we just haven’t found them yet.

And we may be running out of time to do so. This rock may be locked away under a half mile of ice, but that ice is increasingly imperiled on a warming planet. “There is a potential that some of these big ice shelves in the future could collapse,” says Griffiths, “and we could lose a unique ecosystem.”

More Great WIRED Stories

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: www.wired.com