The Death card doesn’t mean literal death, except when it does. Typically, it represents an ending, which also implies a new beginning. Something has changed, or something will change. You just don’t know what yet. Unless you do. Tarot’s funny that way.

The “actual” meaning of the Death card is something you learn when you study tarot, but it’s also something that has slipped beyond the world of tarot lore and into the mainstream consciousness. The TV Tropes page for tarot motifs reveals dozens of mentions of the Death card, most of which involve characters who learn that it foretells “change” or “an ending” instead of literal death.

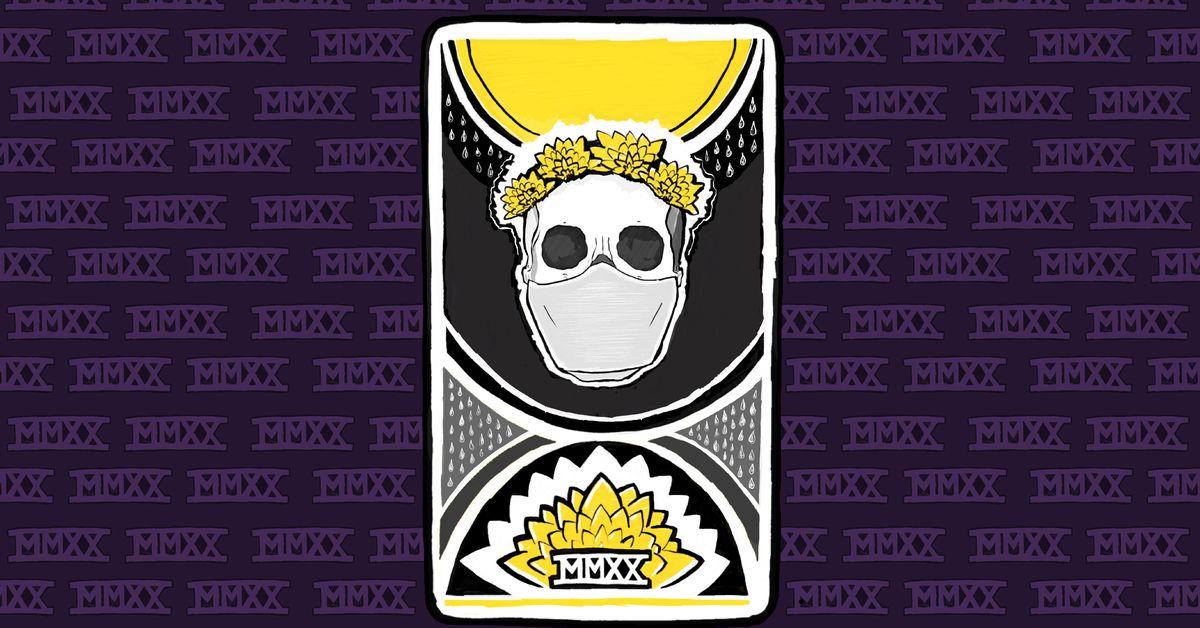

Usually, the Death card features some sort of skeletal figure; the most famous version shows a skeleton in a suit of armor astride a horse. A king kneels before him, because, well, Death is the great leveler. My favorite version, from a tarot deck known as the Brady Tarot, features a human skull with plants sprouting from the eye sockets. Beneath it, the skull of a prehistoric animal rests below the earth, trapped in a giant, all-devouring maw lined with teeth. The saber-toothed cats are gone; humanity will be too someday. Everything changes. Everything is temporary.

I’ve drawn the Death card quite a bit in 2020. And I’ve frequently drawn it reversed, which is to say upside down. Not every tarot reader finds added meaning in reversed cards, but I often do. Typically, a reversed card is interpreted as the mirror image of itself — not precisely a direct opposite, but not not an opposite either. I tend to read Death reversed as stasis, an unwillingness to change, an unwillingness to accept that things end.

Most recently, I drew the card when thinking about this very essay. The question I asked as the starting point for my tarot spread was, more or less, “2020: What’s up with that?” And when I arrived at the slot reserved for “hopes and fears” — because usually our hopes and our fears are closely intertwined — I drew Death reversed. What I feared most was also what I hoped for most: that once this terrible year is over, nothing will have changed.

An idea has taken hold among many of my friends and family that 2020 is a sort of “lost year” that we simply won’t get back. I think I understand this. Early in quarantine, I made list after list of things to do “after all of this is over.” It’s December, and it still isn’t over.

I remember the naive optimism so many of us had in those early days. I remember thinking, the night before Los Angeles’s shelter-in-place orders went into effect, that I should still try to see a movie I had bought tickets to several days earlier. I didn’t go, believing that theaters would be open again by the end of May, if not the end of April. Theaters in Los Angeles still aren’t open. I desperately miss going to the movies.

The movies aren’t all I miss, of course. I see my friends — in person but at a distance, or virtually, from time to time — but I haven’t been able to hug them or hang out in the same way we used to. I miss hugs. I miss the intimacy of a quiet, unmasked conversation in a physical space. I miss going to my favorite bar, a little hole in the ground that serves great sandwiches, homemade potato chips, and absinthe. I miss petting random dogs. I miss traveling.

But missing things is not the same as losing them. To be sure, some of what I miss might actually be gone forever. The movie theater industry is certainly flailing, and many local bars and restaurants will never reopen. But, like, hugs will come back.

The world is not gone. It’s just different.

I started doing tarot during quarantine, as a coping mechanism, when the slow stress of being stuck inside with myself and my thoughts started to eat away at me. Tarot gave me a way to feel grounded. There were always 78 cards in the deck, and they felt like a miniature, bounded universe of their own. Each had a story attached. I could learn and master those stories. I could build a whole world in a single shuffle.

In isolation, I felt, too often, like I didn’t exist. As a trans woman, there is an immense power to being out in the world, to having people see me for me and know who I am. Suddenly, it was as if I had been forced back to 2013, a few years before I came out to myself and a time when I rarely left my apartment and often struggled to leave my bed, so great was the disparity between my body and my brain. Even now, with everyone wearing masks, it’s easy to feel like we aren’t truly seeing other people. To keep each other safe, we have hidden ourselves away.

Since the pandemic began, I have felt completely powerless and out of control. It’s like I was picked up by a malign wind and thrown into the sky with little regard for where I might land. Nearly everyone I know has experienced some variation on this feeling in 2020. We are trapped by chaos.

The thing about yearning for control is that it’s rarely about having control of a situation. Instead, it’s about having control of yourself. I bucked against this idea when my therapist presented it to me. I didn’t want to adopt coping strategies that could help me get through the bad times. I wanted to attack the problem at its source. But I didn’t have any control over its source. And I did have control over the way my thoughts might spiral in any given moment.

So now, when life feels too intense, when trauma rears its ugly head, when I’m just having a shitty day, I pull out my tarot deck and sort it into six smaller decks of 13 cards each. I shuffle them together. I sift through them until I feel certain I have the right card. I turn it over. I see what it is. I tell a story to put boundaries back around the chaos.

A lot of being human is knowing just enough to be terrified of what you don’t know. So we spend a lot of our lives looking at the world through interpretive lenses. Science is one such lens, religion another. Art is a lens, and so is politics. No single lens explains everything, but if you stack enough of them on top of each other, you might start to see a sliver of the full picture.

All belief systems are interpretive lenses designed to assuage our natural curiosity about why things are the way they are, and the discomfort we often feel in the face of uncertainty. If I have a question about the world around me, I can certainly consult science for an answer. But explaining the neurochemical reactions that might make me fall in love doesn’t explain how profound and beautiful falling in love can feel. It’s good to know those neurochemical reactions exist; it’s just as good to find words to express the kind of fragile hope a new relationship or a new friendship can foster in the heart.

Tarot, for me, is a lens. The cards originated as playing cards, with a deck containing 78 cards in total. There are four suits composed of 14 cards each, then 22 more cards depicting specific characters, archetypes, and concepts, which are set aside and known as the “Major Arcana.” (Death, for instance, is No. 13 in the Major Arcana.)

Tarot cards were not argued to possess divinatory properties until long after they had been invented. Humans keep looking for ways to read the future by looking for patterns amid chaos. Why not look for those patterns in playing cards?

But forget about telling the future. Play around with tarot cards long enough and you might start to realize that what they’re really useful for is learning things about yourself. Try to read a story into them and you might trick your brain into letting go of its typical thought patterns, at least a little bit. It’s an end run around consciousness, a way to tap into the place that conjures up your dreams. I do not believe that tarot cards can tell the future because I don’t believe anything can tell the future. I use tarot not to reveal what’s coming, but to reveal where I already am.

A good friend of mine describes tarot as “something between you and the universe,” and that’s why it can feel so sacred to those of us who practice it. There is a person inside all of us that we don’t always want to talk to. (Trans people understand this deeply.) Tarot can get you to a place where you’re talking to that person, maybe even building a relationship with them.

So, some nights, I get out my tarot deck, and I knock on it (to invite my energies into it — I love the ritual of this practice), and I spread out some cards in front of me. They are not evil, as I was taught for so much of my fundamentalist Christian childhood. They are just cards. They almost never tell me anything new. They remind me of what I already know I need to do but am avoiding. Prayer functions similarly; if you don’t believe in God, prayer is just talking to yourself.

That doesn’t mean there’s no value in talking to yourself. Words spoken into empty air are still words. Cards spread out on a table before you are still cards. When I read tarot, I am conducting my own kind of experiment, journeying deeper into myself and figuring out what I might be hiding away until such time as I need it. Belief is not a new way of thinking; it is a new way of seeing.

In the tarot spread I did before I wrote this piece, the one that featured Death reversed as the card expressing hopes and fears, the final card I drew — known as the “outcome” card, which is to say the “in conclusion” card — was the eight of pentacles.

Pentacles are one of the four suits in tarot (the other three being wands, cups, and swords), and they are the suit associated with the element earth (because each suit is associated with one of the four elements). As such, pentacles often represent stability, solid foundations, and the material realities of our lives. The spirit and the soul might be crucial, but you need to feel a sense of physical security before you can really start pondering those loftier matters.

Most designs for the eight of pentacles feature someone sequestered from society, working intently at some important task. The world may be going about its business outside, but they are here, inside, focusing on the work that must be done to make their lives what they want. I don’t know that this characterization will resonate with you, but it certainly does with me. The world hasn’t disappeared, but for a lot of people, it’s been put on hold. Until I can get back to it, I’m going to keep doing important work in solitude.

What form that important work takes is different for everyone who might embrace my interpretation of this card. Maybe, like me, you learned to bake bread this year, and maybe you’ll carry that forward into your life. Maybe you finally read a book you’d always meant to read, or watched every episode of a TV show you’d been saving for a year of rainy days. Maybe you just stayed alive. These are all important works, often done alone.

But my conclusion doesn’t have to be your conclusion. The beauty of the lenses we use to see the world is the way they shift to fit the person who’s looking through them.

I have always been intrigued by tarot, but I don’t think I ever would have gotten into it without this year stuck inside, alone with my thoughts. Some combination of the trepidation that my childhood religion programmed into me and a lack of initiative kept me from really exploring it. When I picked it up, I went all-in. Quarantine, for me, was a chance to connect with pieces of myself I didn’t realize were there until I sought them out. Locked away at home, I started to better understand my own thoughts.

I know so many people who better learned to understand themselves when locked away at home this year. I know even more who spent the pandemic unable to quarantine, for professional or personal reasons. It is not lost on me that my story — one of being able to work from home and focus on myself and my health, both physical and mental — is not universal. If my quarantine doesn’t describe yours, that’s only natural. It’s been hard enough simply to survive.

I also don’t want to minimize the actual losses of 2020. Hundreds of thousands of people have lost their lives to a terrible disease made worse by some combination of government indifference and personal irresponsibility. This has been a terrible, terrible year, even beyond the pandemic, with seemingly 500 major news stories hitting every other day. There was a presidential election, and then the sitting president (who lost) kept feigning that he might try to hold on to power by any means necessary, and many days, it wasn’t front-page news simply because so much else was happening. (You might have forgotten that he was also impeached this year.)

There is a reason the card I drew to symbolize both hope and fear was Death reversed. Yes, I want to know that the world as I knew and loved it will return in some form in the years to come. But I’m also afraid that we will learn nothing from this experience, that we will, instead, hurtle so quickly back to our lives as they were that nothing will change in a world where so many things need to change.

On a societal or global level, that lack of change might really come to be. But on a personal level, I’m much more hopeful. For as hard as this year has been, so many of us have discovered things about ourselves we didn’t realize were true. There are so many stories of 2020 that are quieter than the headlines. Personal revelations and instances of people looking out for each other kept happening alongside the turmoil and tumult. You just had to know where to look for them. So I went looking, and I have been so enthralled by what I’ve found. Over the next few weeks, I’m going to tell some of those stories.

This has been a lost year in some ways, but also a year of learning, of bonding, of growth. Stories of grief and sorrow are important to tell, but so are stories of joy and connection and life. We will always look back on this year and remember what was hard. I want to remember what was good, too.

A story:

Sometime this summer, I was taking a shower, crying in exhaustion and anxiety from the extreme stress of, well, everything.

That very day, a friend had sent me some flowers, because she knew I was having a hard time. Seeing them, bright and joyous and colorful, had reminded me that everything ends, and everything changes. Flowers, by their nature, are fleeting. But they’re beautiful for a time.

I looked down at the floor of the tub and saw a soggy yellow flower petal stuck there. I felt a thrill at the thought of finding this obvious symbol of my friend’s love for me in the midst of my stressed-out solitude. Intellectually, I knew I had tracked the flower petal into the tub on my heel, but it felt magical, an answer to a prayer for comfort I hadn’t thought to utter.

I stooped to pick up the petal, only to see it wasn’t a flower petal at all. It was a yellow Starburst wrapper I had not seen properly in the dim lighting of the bathroom. I had somehow dragged it into the shower with me. I deflated. I had missed the obvious truth in front of me.

And yet —

Even in the stark isolation of 2020, it was worth remembering that tumult and despair I have felt so often this year is not the only reality there is. Even if what I saw on the floor of the tub wasn’t a flower petal, the way I saw through the exact lens I needed to see through, precisely when I needed to see through it, was still real.

The flower petal was “really” a candy wrapper. But it also was a flower petal. It had transmogrified itself in the moment I needed it most. Neither I nor you can prove it did not, even as we know it did not. How you see a thing is always a matter of what you hope to see.

Thus endeth the lesson.

For the next three weeks, I will be sharing stories of people’s very real experiences in 2020, had against the backdrop of the pandemic, from all over the globe. On Thursday: a woman, an injured baby pig, and a series of revelations.

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: www.vox.com