Uncrewed submarines have been diving into the hadal zone for decades, but Brennan Phillips, an ocean engineer at the University of Rhode Island who specializes in remotely operated and autonomous deep sea robotics, says it’s hard to beat a human when it comes to exploring the seabed. For starters, humans can see more. Our eyes are amazing sensors and modern underwater cameras—or any cameras, for that matter—can’t come close to matching their resolution, especially in the low light of the deep ocean. “I’ve been in a manned submersible in the deep ocean and seen things with my own eyes that you can’t repeat yet with a camera,” says Phillips. “They’re still a long way short of what the human eye can do.”

Humans are also important for discovery. Scientists cruising the seabed in Alvin are better equipped to recognize something they’ve never seen before and take a sample of it to study once they’re back on the surface. While this can also be done with a remotely operated sub that is connected to a human controller on the surface via a long tether, it’s more challenging for remote operators to identify promising sample sites. The miles-long tether can also create problems for the robot and limit where it can travel. Untethered autonomous robots have a harder time still, since they don’t have access to GPS for guidance and can struggle to recognize promising sample sites on their own.

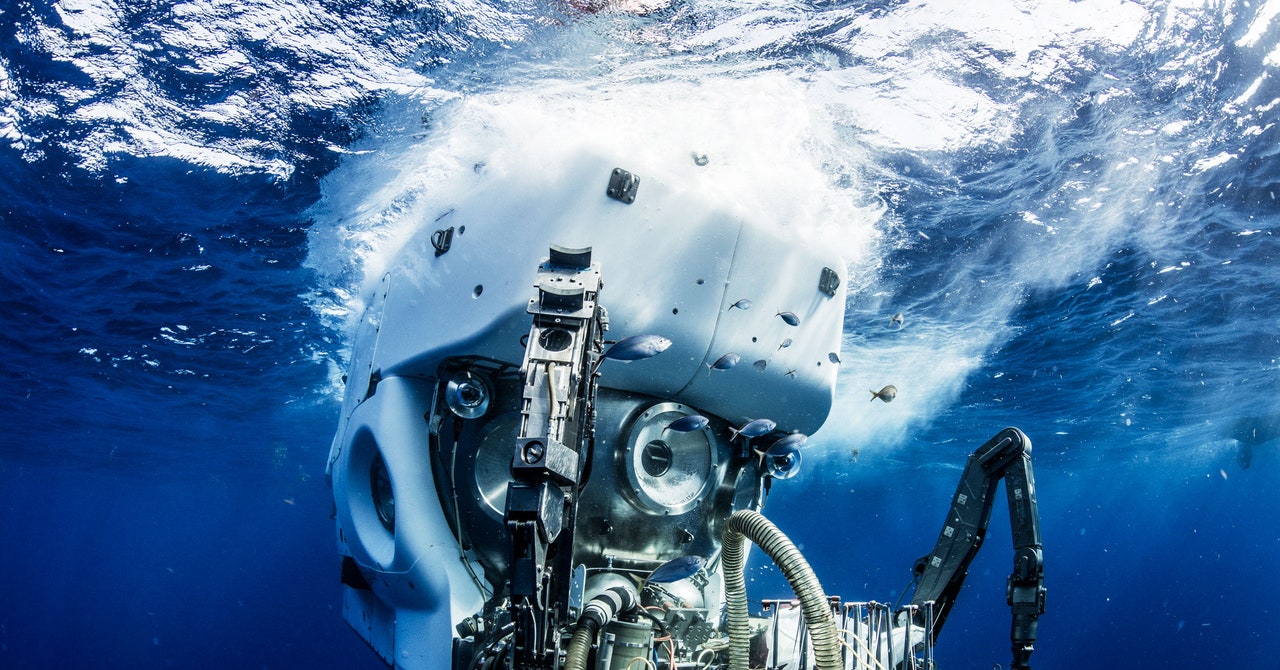

Phillips thinks that relying on robots might also compromise what scientists can see in the deep ocean. They tend to be much louder than subs built for humans, and they use much brighter lights because of the limited resolution of their cameras. Phillips says this likely frightens bottom dwellers, which makes it harder for researchers to make new discoveries. He suggests that part of the reason the hadal zone appears so desolate is because by the time these lumbering robots get to the bottom, they’ve scared away all the inhabitants.

“There’s only been a handful of dives to these depths, so we really need to go more often,” says Phillips. “The hadal zone is considered to be basically featureless, but some of that might be coming down to our methodology. If you just make it a bit more stealthy, you can probably find things down there that we’ve been missing this whole time.”

After 25 years of roaming the seafloor in Alvin, Strickrott isn’t afraid of a robot taking his job anytime soon. He acknowledges the important scientific reasons for keeping humans in the loop, but for Strickrott, human-driven deep sea exploration taps into something more profound. While many people might not relish the idea of being trapped in a cramped metal bubble in the pitch blackness of the deep ocean, Strickrott says that’s his “happy place.” He can still recall the thrill he had working on Alvin as a young ocean engineer, and he relishes accompanying budding marine scientists on their first trip to the bottom of the ocean.

“There is, without a doubt, this really aspirational part of oceanography that involves humans exploring these parts of our planet that have never been seen before,” says Strickrott. “In order to keep the science of oceanography vibrant, we need to ensure that there are lots of people who are excited by the science.”

Strickrott feels that establishing that connection with the ocean—by immersing yourself in it, by going as deep as you can in this alien environment, by seeing how life can thrive in an environment that would kill land dwellers instantly—is critical to its future and our own. We may need cutting edge technology to survive a trip into its depths, but the ocean and life on land are deeply intertwined. It’s that connection that Strickrott channels each time he climbs into Alvin. “Once you’re underwater, you get into this place in your mind that’s sort of Zen,” he says. “You’re part of the system.”

Update 12.21.2020 5:43 PM: This story has been updated to correct the number of people who have traveled to the bottom of the hadal zone.

More Great WIRED Stories

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: www.wired.com