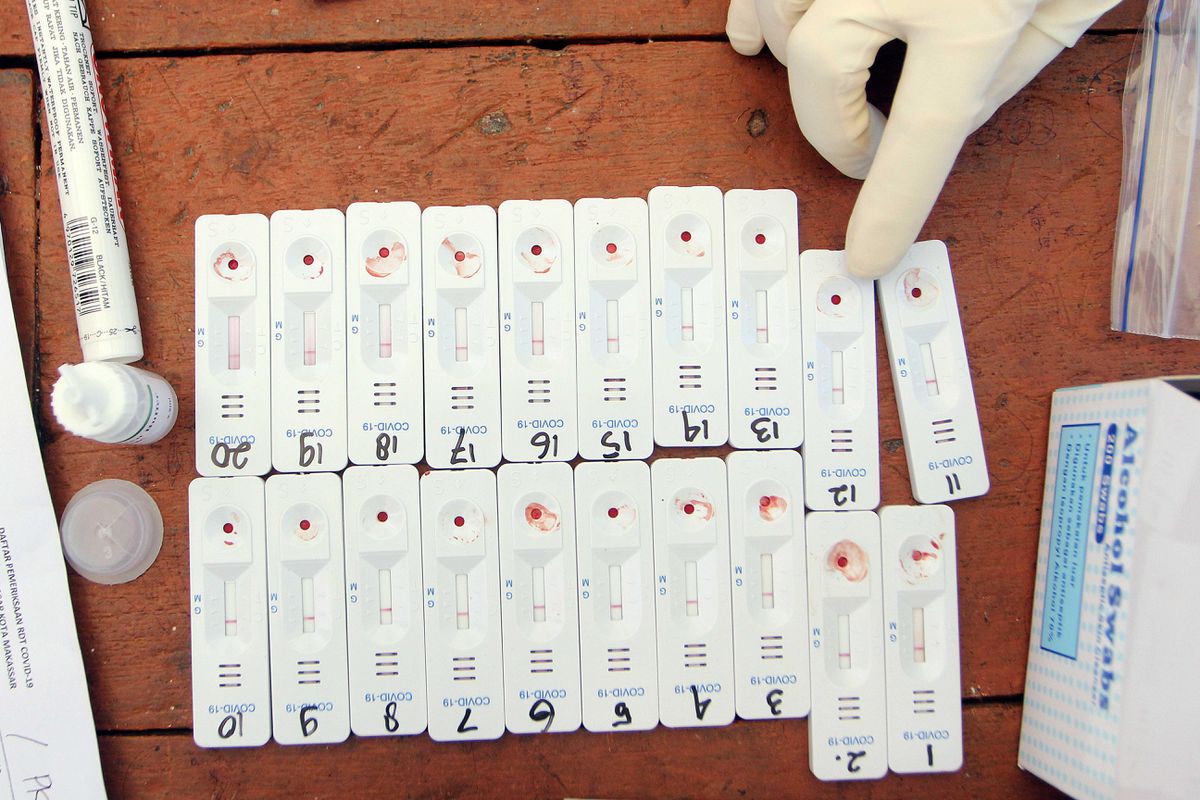

A medical officer show Rapid Test Covid-19 result at Pabaeng-baeng tradtional market amid concerns … [+]

Barcroft Media via Getty Images

Diagnostics have always received little attention in global health, in comparison to drugs and vaccines. But the Covid-19 pandemic has shown the world the critical importance of early and rapid diagnosis, for clinical management of illness as well as for containing outbreaks.

On 29th January 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the third edition of its Model List of Essential In Vitro Diagnostics (EDL). This edition includes WHO-recommended Covid-19 tests (nucleic acid as well as antigen detection tests), expands the suite of tests for vaccine-preventable and infectious diseases and non-communicable diseases (such as cancer and diabetes), and introduces a section on endocrinology. Country governments must now adopt and adapt the WHO EDL, to ensure improved access to diagnostics in countries.

Rationale for an EDL

Analogous to the WHO Essential Medicines List (EML), the EDL is a package of recommended tests that should be available in every country, at various levels of the healthcare delivery system (infographic). Access to tests matters, since diagnosis is the first step to correct disease management and containment of outbreaks. “Access to quality tests and laboratory services is like having a good radar system that gets you where you need to go. Without it, you’re flying blind,” said WHO Director-General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

WHO essential diagnostics list (Source: … [+]

World Health Organization (WHO)

“More than ever, as we go through this pandemic, we see the importance of diagnostics, and how we run blind in the face of illness, if we don’t have accurate, easy-to-use, and affordable means to diagnose early,” said Mariângela Simão, WHO Assistant-Director General for Access to Medicines and Health Products, speaking at the launch event webinar.

What’s new in the third edition?

Speaking at the launch event, Mercedes Perez Gonzalez, a WHO staff member in the EDL Secretariat, shared the key highlights of the third edition. She explained the process by which the EDL was updated by the SAGE IVD advisory group, and shared that the list now contains 175 test categories, plus two Do Not Do recommendations. New tests added to the list include Covid-19 tests (nucleic acid amplification and antigen detection tests), tests for endocrine disorders (e.g. cortisol, prolactin, follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estradiol), point-of-care sickle cell test, Aspergillosis, Pneumocystis PCR, tests for measles and rubella, Group A streptococcal rapid test, among others.

Do Not Do recommendations are meant to advise countries against the procurement and use of specific IVD categories. Two tests are currently included in this category: HIV western blot, and serodiagnostic (antibody) tests for diagnosis of tuberculosis.

Like the previous EDLs, tests in the the third EDL are categorized as: 1) tests for use in community settings and health facilities without laboratories; and 2) tests for use in clinical laboratories. The EDL includes product classes, but does not specify or endorse any commercial brands.

At the launch event, Adriana Berumen Velazquez, a senior WHO staff member, unveiled a new, highly informative WHO website that is dedicated to diagnostics, and also demonstrated a beta version of an eEDL, an electronic, easily searchable version of the EDL. A new video (below) on the importance of diagnostics and EDL was also screened at the event.

Global health experts received the latest EDL edition with enthusiasm.

“Our work for the Lancet Commission on Diagnostics has shown that lack of diagnosis is the biggest gap in the patient care pathway globally,” said Kenneth Fleming, a professor at Oxford University, and Chair of the Commission. “This is the result of long-standing failure to prioritize and allocate appropriate resources for diagnostics. Addressing this will take years, but the 3rd edition the WHO EDL is a major step. As countries provide the diagnostics listed across their health systems, especially at the primary health care level, this will go a long way towards the Commission’s aim of ensuring equitable access to accurate timely diagnosis,” he added.

“The release of the first EDL in 2018 was a long-overdue milestone that acknowledged how truly essential diagnostics are to health system efficiency – a point that has been painfully underlined by the Covid-19 pandemic,” said Sergio Carmona, Chief Medical Officer at FIND, Geneva, a non-profit that is dedicated to diagnostics. “This third edition is another vital step that paves the way for countries to develop national EDLs that are adapted to their specific needs and context. We applaud India for leading the way with the first national EDL, and encourage other countries to follow suit and prioritize testing as the bedrock of their own health systems,” he added.

“I’m excited that there is a palpable momentum with the EDL – with the launch of the third edition of the EDL, release of the beta version of electronic EDL, and creation of the new EDL website. Next steps must be supporting national EDL implementations,” said Lee Schroeder, an associate professor of chemical pathology at the University of Michigan, who contributed to the WHO SAGE IVD advisory group.

“The addition of some cancer and diabetes diagnostic tests to the EDL will help countries move a step closer to earlier disease detection, saving lives and substantial costs,” said Rachel Nugent, VP for global non-communicable diseases at RTI International. “Cancer care in low-resource settings requires early and selective testing to achieve good return on investment,” she added.

Reacting to the launch of the 3rd EDL, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) welcomed the addition of WHO prequalified Covid-19 tests to the 3rd edition. “Listing is one thing but all countries should have equal access to WHO quality assured Covid-19 tests,” said Stijn Deborggraeve, a Diagnostics Advisor at the MSF Access Campaign. “Fair supply and fair prices to lower- and middle-income countries is absolutely essential for the much-needed scale up of Covid-19 testing in settings that lack the testing capacity and test supplies that are available in wealthier nations,” he emphasized.

Lists do not deliver themselves

Laboratory infrastructure in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is very weak. So, there is no guarantee that WHO EDLs will translate into real access for patients on the ground.

Indeed, small-scale studies in India, Peru and Ethiopia have used the WHO EDL as a benchmark to assess if healthcare facilities have the package of essential tests. All studies found big gaps between what should exist in clinics, versus what tests actually exist.

Cesar Ugarte-Gil, a professor at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Lima, Peru, led one of these studies. “Based on our research in Peru, none of the tests in the WHO EDL was available 100% at all the facilities we surveyed,” he said. He considers the WHO EDL a good “checklist” for countries to identify and address gaps in the diagnostic system.

While WHO EDL has rapidly grown and matured in 3 years, the action now must shift to countries, especially LMICs. It is when LMIC governments adopt, adapt and implement the WHO EDL, real progress will happen.

Countries now must lead the way

WHO model lists are intended to provide guidance to countries. Based on national disease burden and health system capabilities, countries can modify and adapt the WHO EDL to suit their priorities and needs. The national EDLs can then be incorporated within universal health coverage (UHC) benefits packages, funded, and implemented at the national level. So far, WHO has worked with Nigeria, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan to support the development of their national EDLs.

“While the WHO EDL provides an excellent reference point, each country needs to create its own list based on the health priorities and what is currently available to deliver diagnostics services,” said Kamini Walia, a senior scientist at the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), which led the National EDL development in the country. India was the first country to adapt the WHO EDL and develop its own National EDL. Implementation is happening via the National Free Diagnostic Service Initiative, a part of India’s National health Mission.

Nigeria might be the first African country to follow this path. “Nigeria, through its Federal Ministry of Health and the National Laboratory Technical Working Group (NLTWG), has made progress with the development of the Nigeria EDL,” said Anthony Emeribe, a Professor of Hematology, at the University of Calabar. The draft NEDL is currently at the last phase of it’s approval and release. “The plan is to integrate the NEDL with the NEML, the ongoing revision of the National Medical Lab Services Policy and the National Medical Lab Services Strategic Plan all geared towards a costed Universal Health Coverage in line with the Nigeria Health Act 2014,” said Emeribe.

“The WHO EDL will have to be adapted to local needs and requirements so as to ensure that the right diagnostic test gets to the right patient at the right time. This will need buy-in from provincial health departments and from communities – medical, professional, and social – to ensure uptake of recommendations,” said Sadia Shakoor, an associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan.

“There is an urgent need for development of a country specific EDL in South Africa, particularly for primary healthcare level diagnostics or point-of-care diagnostics to improve the reach of essential diagnostics to the whole population,” said Tivani Mashamba-Thompson, a professor at the University of Pretoria. She argued that any national EDL must account for the fact that “South Africa has a quadruple burden of diseases, which include both communicable and none-communicable diseases coupled with the Covid-19 pandemic as well as limited laboratory infrastructure.”

Even as the Covid-19 pandemic continues, it is clear that more countries need to leverage the WHO EDL, develop their own national lists, and plug the access gap in diagnosis, not just for Covid-19 but for all critical health needs. To facilitate this, WHO will soon publish a step-by-step guide to aid countries planning to develop a national list.

Disclosure: I have no financial or industry interests in any diagnostic company or product. I previously served on the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on In Vitro Diagnostics (SAGE IVD) group that developed and updated the Essential Diagnostics List. I serve as an advisor to the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), a non-profit agency that works on diagnostics for diseases of poverty. I have conducted research on access to diagnostics using EDL as a benchmark.

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: www.forbes.com