A winter tree battered by the the winds.

getty

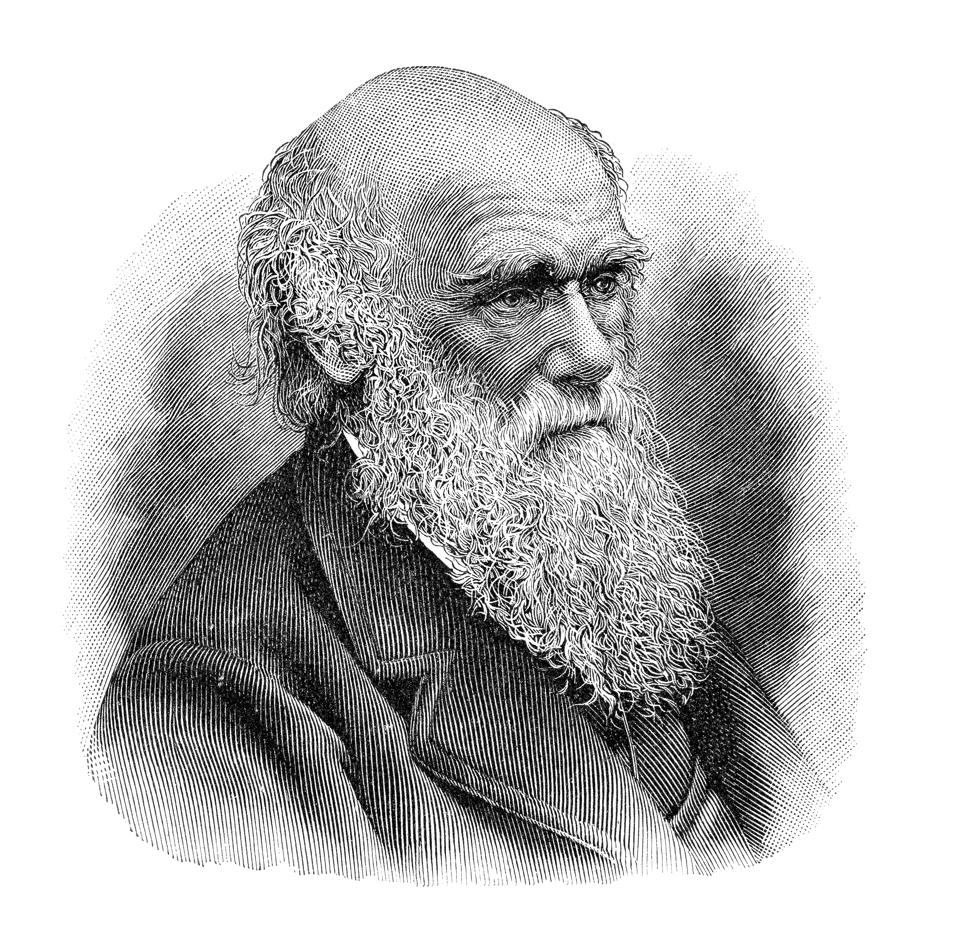

About 95% of insect species worldwide can fly. The question of what environmental pressures determine whether or not an insect species evolves to have wings has long fascinated scientists. The first known scientist to be intrigued was the twenty-two-year-old Charles Darwin when, in January of 1831, he visited the Portuguese-held island of Madeira off the coast of Morocco.

(Echium candicans or Echium fastuosum) is a rapidly growing tropical or tender perennial/biennial … [+]

getty

The island of Madeira is part of a volcanic archipelago. On its dramatically rocky shoreline, northeast trade winds bring in huge ocean swells. Temperatures at sea level in Madeira average in the 50s and 60s (F) in the winter, and are only a little warmer in the summer. In the windswept mountains it can snow. Because of its microclimates and isolation, Madeira is home to a wide array of endemic species like the Madeiran long-toed pigeon with its six-note cooing and the endangered Zino’s Petrel, a seabird that lives exclusively at sea and only returns to the island to breed in the mountains. Madeira also has twenty-four species of endemic land mollusks, and it has lots and lots of beetles. Darwin was a beetle afficionado. On Madeira, he collected them, and noticed that, unlike any other beetle he’d ever seen, they were wingless.

Steel engraving of naturalist Charles Darwin.

getty

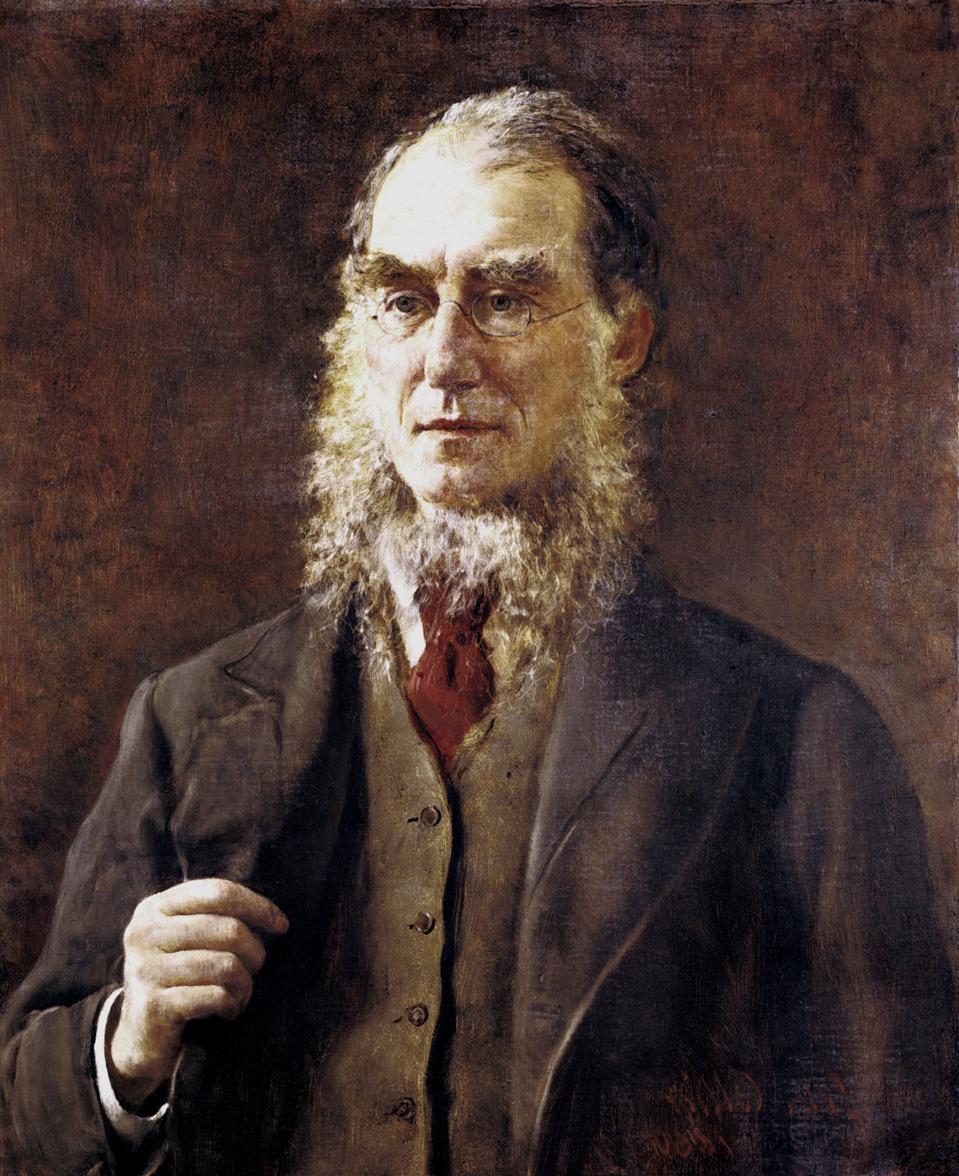

Twenty-five years after his trip to Madeira, Darwin mentioned the wingless beetles to his best friend Joseph Hooker, a geographical botanist and an adventurer who, like Darwin, had voyaged to Madeira in his younger years. To Hooker, Darwin hazarded a guess about how the “apterous” (un-winged) beetles had evolved. Roughly, what he suggested was that Madeira is a small island with strong winds. Any flying insects would probably have gotten blown out to sea, leaving the flightless ones to dominate the gene pool. Hooker responded that he thought Darwin’s idea to be “very pretty.” At the same time, he pointed out that he had found wingless beetles in the Sahara Desert, which is nowhere near water.

Joseph Dalton Hooker

getty

And so a friendly argument began. Darwin and Hooker never resolved it, and it has persisted among scientists from 1855, the year of the two scientists’ discussion, to 2020. Publishing this December in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, researchers from Australia’s Monash University have finally settled matters. Drawing on information about insects, microclimate, and habitat stability, they have demonstrated that Darwin was right — at least in identifying wind as the cause of the evolutionary change.

The data used by the Monash University team had been systematically culled by researchers working on Antarctica and on the twenty-eight Southern Ocean Islands located about halfway between Antarctica and Australia. Those islands are renowned for their wind speed. According to the U. S. National Ocean Service, during the Age of Sail (the 15th to 19th centuries) the winds between Australia and the South Pole “propelled tall ships across the ocean at breakneck speed.”

The Monash University researchers applied every credible hypothesis about the evolution of apterous insects to the insect, habitat, and microclimate information in the database. These theories included:

Dunes formed by wind in the Sahara Desert, Ouargla. Algeria.

getty

· Wind, freezing temperatures, or low air pressure might independently increase the energy required to fly, depriving insects of the energy to manufacture healthy sperm or eggs, to find a mate, or to mate at all once a mate was found. Only insects that opted not to fly might have been left with the energy to reproduce well.

· Habitat fragmentation might deprive insects of the motivation to fly.

· The disappearance of either predators or competitors from extraordinarily uncomfortable environments might make flying unnecessary for insects.

· Wind might blow the insects off the island (Darwin’s idea).

And a few more.

Combing the databases, the researchers found that nearly half (47%) of insect species that evolved on the Southern Ocean Islands archipelago near Antarctica have no wings. That is an exceptional number, representing nearly ten times the worldwide incidence. Comparing variables about microclimates, island insularity, and habitat to the incidence of wing-lessness in insects, the team found that Darwin was probably wrong about one matter. The proportion of flightless insects on an island doesn’t generally scale with island size; insect populations are not decimated and their species fundamentally changed because the bugs that fly get blown out to sea. However, wind speed, habitat stability, and summer land surface temperatures together correlate with 77% of wing-lessness.

A traditional tall ship with reefed sails sailing through rough seas in the southern pacific ocean.

getty

The team also found that wind speed has the single strongest correlation to the proportion of flightless insects. Indeed, they noted that the windier the island, the more flightless insect species they identified.

In the end, the team from Monash University recognized Darwin as having been right in identifying wind as the primary driver of insect evolution away from wings and flying. Even so, they were not willing to credit him for pinpointing precisely what it was about the wind that steered the evolutionary path. Where Darwin had suggested to Hooker that the wind tossed insects off of islands, the Monash University researchers suggested that, in environments that are very windy (like Madeira, the Sahara Desert, and the islands near the southern tip of the world), the energetic cost of flying is simply far too high. Darwin had specified that all organisms are driven by a biological imperative to ensure the survival of their particular genome into subsequent generations. If he was right, insects are much better off expending their physiological and caloric resources on the machinery and quests of reproduction than they are trying to fly in impossible environments.

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: www.forbes.com