Pakistan started confidently, and none of the Indian bowlers were able to make an impression. At lunch, with the visitors at 101 for no loss, the Indians were despairing that they might actually lose the Test.

In 1897, American author Mark Twain on learning from ‘a good authority’ that he was dead, sent a response to a New York Journal reporter that read: ‘The report of my death was an exaggeration.’

Test cricket, that took its first baby steps in the form of the Ashes two decades before Mark Twain wrote those words, would spend the next 140+ years dispelling rumours about its own demise.

It is largely thanks to the Ashes, along with two other matchups, that the sad ending so often predicted for Test cricket, has not come to pass. The first of the two is the intense battle over 22-yards for the Border-Gavaskar Trophy that has blessed the sport these past decades. The other, India versus Pakistan – a rivalry that transcends sport and has its roots in politics and tragedy of partitioning a great nation into two disparate halves.

It is the last that gave the world of cricket one of its most significant moments in the winter of 1998–99, when Pakistan visited India for the first time in 12 years to play a Test series.

Heartbreak in Chennai

In the first Test that lived up to every bit of the pre tour hype, Pakistan beat India by 12 runs in Chennai. It remains one of the more evenly contested Test matches in history. Pakistan scored 238 in the first innings with Moin Khan stroking his way to a plucky 60, while Anil Kumble took six wickets. India responded with 254. The highlights were a top score of 54 from Sourav Ganguly, and Saqlain Mushtaq’s five wickets.

In the second innings, Pakistan responded with 286 on the back of a magnificent 141 from the mercurial Shahid Afridi. At 254 for six, India stood at the cusp of a famous win. At the crease was the ever dependable Sachin Tendulkar.

Battling significant back pain, Tendulkar then took a fateful decision – to score the remaining runs quickly so as to hasten the inevitable victory. Unfortunately, his attempt to go for a third successive four against the guile of Saqlain Mushtaq, failed to come off. A catch to Wasim Akram was the result.

With a win just 17 runs away, as a billion fans sat glued to their television sets around the country, hearts firmly in their hands, the Indian batting spectacularly unraveled. The last four wickets added only four runs before the innings folded up. Once again, India had snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.

First blood in this gladiatorial contest had gone to Wasim Akram’s Pakistan.

Magic at the Kotla

Then the teams came to the Ferozshah Kotla in Delhi, with everything to play for. A draw meant that Pakistan would retain the trophy, having won the last series in 1987. For India, nothing but a victory would do. It was not just for pride, but because the team knew that at Chennai, they had thrown away their best chance to win a Test against Pakistan in 20 years.

When Azharuddin won the toss, the decision to bat was an easy one. Facing an attack consisting of Akram, Waqar and Saqlain in the fourth innings was an experience the team was not keen to repeat.

Sadagoppan Ramesh and VVS Laxman opening the innings took the score to 88. Just as the smiles were starting to spread on Indian faces, a beautiful in-swinging delivery from Akram found the gap between Laxman’s bat and pad. Ramesh batted on to score 60 and Azharuddin joined him, contributing 67. India was dismissed for 252, Saqlain once again taking five wickets on a pitch where the ball was already keeping low.

The start for the visitors was less than ideal. Saeed Anwar fell to a beautiful swinging delivery from Venkatesh Prasad that found the edge of his bat. Pakistan one for one. Afridi and Ijaz Ahmed took the score to 54 before both fell at that score. Saleem Malik added 31 before the side was dismissed for 172. Kumble had picked up four wickets and Harbhajan Singh pitched in with three. India had a lead of 80 runs.

Kumble would say later: “The pitch was a bit two-paced and we knew that if we could keep them quiet, we would be able to get them out.” He knew the onus would be on him to deliver on his strategy. What he didn’t yet know, was the extent of that dependence.

India’s second innings got off to an inauspicious start. With the team score at 15, Laxman was bowled through the gate by Akram in a virtual action replay of the first innings dismissal. Dravid and Tendulkar then made an appearance in the supporting cast, with Ramesh, in only his second Test match, playing the lead role. It would turn out to be the innings of his life.

Ramesh was finally dismissed for 96, but Sourav Ganguly was there to steady the innings with a score of 62 not out. In the company of first Kumble and then Javagal Srinath, Ganguly guided India to a score of 339.

While Ganguly attacked the Pakistani bowlers, Srinath at the other end had put on a gritty 49. He would say later: “I held myself responsible when we lost the Chennai Test by 15 runs. So this time I wanted to bat for longer and managed to combine well with Ganguly that set up a good target.”

With two days to go in the Test, Pakistan was left to score 420 to win the Test. It was a challenging task, but something that had been done before. The Test, and the series was set for an exciting finish.

A Day to Remember

Pakistan started confidently, and none of the Indian bowlers were able to make an impression. At lunch, with the visitors at 101 for no loss, the Indians were despairing that they might actually lose the Test.

At this stage, coach Anshuman Gaekwad decided to take Azhar aside for a chat. “I had a chat with Azhar. I told him the only person at that juncture who would go through Pakistan on the Kotla pitch was Anil. So we had to take chances with him by making sure he did not get tired. Azhar handled Anil tremendously well and needs to be given credit,” recounts Gaekwad.

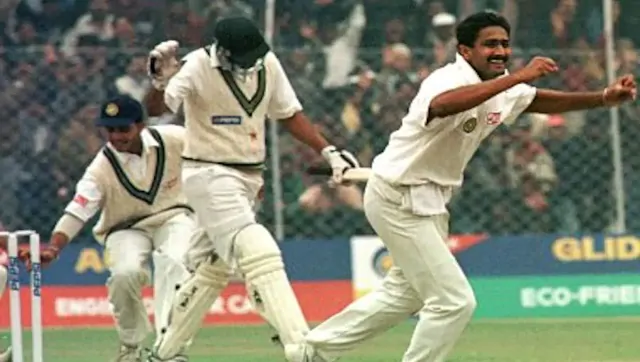

After lunch, with the Pakistan score still at 101, in what would turn out to be an inspired decision, Azhar switched Kumble, whose figures that morning had read 0 for 27, to the Pavilion End. The effect was akin to switching on the brilliance of a hitherto malfunctioning spotlight on a Broadway stage.

Afridi tried to drive a ball outside the off stump that held its line, and the faint edge carried to Mongia. Afridi held his ground, but was finally forced to walk off. Kumble would say later: “Who walks? Nobody walks. It was a big nick. That wicket started everything and I knew it wouldn’t be easy for the rest of the batsmen.”

Ijaz Ahmed was next. He got a ball that thudded into his boots on the full toss at yorker speed. Inzamam avoided the ignominy of conceding a hat-trick, but his defiance would last only for two balls and a beautiful cover drive. Then, displaying the same “lazy elegance” that had marked his four on the previous ball, he directed a trademark Kumble ‘straighter one’ on to his stumps. Yousuf Youhana followed a couple of balls later, trapped in front of the middle stump.

Suddenly, Pakistan was 115 for 4. But Azhar and his men knew that it was too soon to rejoice. For still out there was India’s long-time nemesis, Saeed Anwar.

While Anwar continued to defend doggedly at one end, Kumble got a leg break to turn and bounce, and Moin Khan could only guide it into the slip area for Ganguly to take a lovely tumbling catch inches off the ground. Then Kumble bowled a similar delivery, but this time to the dangerous Saeed Anwar who helplessly watched the ball spoon up off his bat. Laxman at forward short leg gleefully snapped up the chance.

Pakistan was now 128 for six and Kumble had six for 15 in 44 balls. “That was the moment when I thought all ten could be mine,” he would say later.

Kumble was dog tired by this time, having bowled continuously between lunch and tea. The tea reinvigorated him, and he came out all charged up to have a go at the last dangerous pair – Saleem Malik and Wasim Akram.

The pair had already put on 58 runs, when Kumble decided to bowl one of his faster balls at Malik. He pitched it short and the ball skid through fast and took out the middle stump. A few balls later Dravid at gully took a catch off the gloves of Mushtaq Ahmed. Saqlain departed the next ball, trapped in front. Kumble had now taken nine wickets.

Javagal Srinath was bowling from the other end. Urban legend has a conversation taking place between the captain and the bowler, but Srinath says later: “Nobody had to come and tell me to not take that remaining wicket. Anil had been bowling well and he was on the verge of a record and it was just a unanimous decision.”

Despite his best efforts, Srinath almost got Akram. VVS Laxman tells me about the whole team screaming at young Ramesh fielding at mid-on: “Don’t take the catch,” when the ball spooned up to him. But it all ended well as the ball miraculously fell in no-man’s land.

Akram was acutely aware that Kumble wanted to give him a single and get Waqar Younis on strike, and refused to fall for that bait. It was a cat and mouse game that could not last forever. Eventually Akram fell to a simple leg break and Laxman completed the honours at short leg, giving Kumble his 10th wicket of the innings. In an unbroken spell after lunch, Kumble had taken a stunning 10 wickets for 47 runs in 20.3 overs. It was the greatest single spell in the history of Test cricket.

Kumble was carried back to the pavilion on the shoulders of his teammates. “My first reaction is that we have won. No one dreams of taking ten wickets in an innings, because you can’t. The pitch was of variable bounce, and cutting and pulling was not easy. All I had to do was pitch in the right area, mix up my pace and spin, and trap the batsmen. The first wicket was the hardest to get…the openers were cruising,” he reminisced later.

Many years later when I first met VVS Laxman I asked him how nervous he was when that last catch came to him. Laughing, he said: “Very! The pressure on me was more than you imagine. It wasn’t only about the single greatest bowling spell in history. Anil was my roommate. I had to take the catch or spend the night outside in the Delhi cold. I didn’t really have a choice you see, I had to take that catch!”

Subscribe to Moneycontrol Pro at ₹499 for the first year. Use code PRO499. Limited period offer. *T&C apply

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: www.firstpost.com