Yu Gu has been directing films for over a decade. Her latest documentary, A Woman’s Work: The NFL’s Cheerleader Problem, follows two women in their fight for fair pay from the NFL — a multibillion dollar industry.

I recently got a chance to talk to Gu about the film, gendered work, and football as her lens into American culture.

DF: I want to start with a little bit about you. I watched the film first. I read about you second. And I’m curious what drew a filmmaker born in China, yet raised in Canada, to do a story about cheerleaders in the most popular sport in the U.S.?

YG: I really didn’t know much at all about football or cheerleading until I moved to America. I went to the University of Southern California for my graduate degree in film. It was definitely a culture shock. You know, people are like, “Oh, Canada, it’s very similar to America.” Actually, I feel like culturally there’s a big difference especially when it comes to sports. Growing up in Canada there was obviously NHL hockey. We had the [Vancouver] Canucks there. But then coming to the States to USC, it was like the height of the Pete Carroll era. And I also tutored football players in English lit. and essay writing. And I could see the cafeteria they use, the buildings they used were just above and beyond any other buildings on the whole campus, even the film school.

G/O Media may get a commission

You could see that they were part of this bigger system that was nurturing them to play football. And that’s what they were obsessed with.

And so I think that became a window for me into American culture, into American values, American history as someone who is a foreigner to this country. From that, I really looked into sort of the narratives of football and just watching movies and TV shows like Friday Night Lights and the amazing values that America espouses that draws immigrants to this country, like the spirit of teamwork and family and what it means to be a true champion and all of those things.

I think all those things are amazingly beautiful. And I get teary every time I hear the American national anthem to an extent, not because I’m such a patriot, but because it represents sort of these dreams that unfortunately we have not yet achieved. And that’s why it’s both beautiful and somewhat poignant at the same time.

That’s basically why I became interested in this story. It was my way in because looking and understanding the cheerleaders who are these women who are icons that are completely devalued in the workplace. On the one hand, they have met the highest standards of beauty and athleticism. And yet, on the other hand, they’re paid very little [or] below minimum wage or even nothing at all. I think that was sort of my entry point into just learning more and discovering more.

DF: I was really struck by the opening. Maybe it’s my own naivete, but I never really heard people in the media [or elsewhere] talk about cheerleaders as part of a team and putting themselves before others, [which is] a critical part of sports. But it’s weird, I feel like I never hear about that when we speak about cheerleaders.

YG: Right. When Lacey and Maria and other women were talking about it, I was really drawn to that. Partially again, because I grew up always feeling like an outsider no matter what it was. I was a benchwarmer. I never felt like that kind of team camaraderie.

When they were talking about that, it just made so much sense to me. There is this built-in camaraderie, right? That, like you said, any kind of team sports really fosters. And I thought that was just amazing. They use words like “we’re a family, where it’s a sisterhood” and, you know, you hear the football players say, “we’re a family, we’re a brotherhood.” And I think you definitely see that. And, again, that’s part of why the women are drawn to it. That’s part of something you get from being a part of that team.

DF: Yeah. So let’s talk about that brotherhood/sisterhood. I thought one of the most brilliant points in the film was when you had this “football is family” montage. I want to ask you to think about that phrase “football is family” and what do you argue a woman’s work is in that family?

YG: Well, I think there’s a couple of different things going on there. You have the NFL slogan “football is family.” And then we also introduced some historical context with the 1950s kind of educational film that explicitly says “the money is the father’s work, and what did my mother do today?” And it was just the perfect illustration of the separation of work according to gender.

And it’s clear that on one hand you have women who are doing the domestic work, who are doing the care work and they don’t get money. And then you have the man who’s outside of the home doing work that apparently is rewarded with money. And I think that’s part of the theme that the film tackles is this kind of dysfunctional, traditional view of gendered work and what that means within the American family.

The women in my film, the main characters, are standing up for the value of their labor, whether it is in terms of being cheerleaders on the football field or even in their personal lives, as mothers, as daughters, as caretakers.

DF: I was stunned to see some of the numbers that you uncovered regarding the pay of cheerleaders. I’m really curious to know what you thought the most surprising statistic from the film was.

YG: That’s an interesting question because I feel like everything was surprising. Looking at [the film] from the starting point of being interested in the culture and mythology of football and then going on this five-year journey of making this film, I feel like I’ve become a student of the institution of football. I think now it’s not surprising, but as I was learning the [pay] disparity was incredible. The fact that the profit of the NFL is divided and shared among the teams and the different owners. And then you have all of the disparity with the players. I think maybe that was pretty surprising. Like, the base player [salary] when I was looking into it was about $420,000.

When you look at cheerleaders and how they’re compared to even mascots who are paid a salary, like a fairly livable salary, for the year. And you have then cheerleaders who only get paid for the [fall] season. Lacey was getting paid like $1,250 or something for the whole season. So I think that kind of disparity was the most shocking to me because of the fact that there is so much money that is then shared by all the owners in the league.

DF: Yeah, I feel like this is a story about really brave women but it’s also a story about a few powerful men. You talk about what it means to be a feminist in the film. So, in your mind, what can men, and reasonable NFL fans everywhere, do to fight for fairness in cheerleading?

YG: In the journey of making this film, I didn’t really see many players engaging in the conversation about fair pay and equality and discrimination that the women and cheerleaders have brought forth. We really haven’t seen that kind of support from the players. It’s a cliche, but everyone is stronger together. Right? So, if that kind of allyship and bridge-building could happen, that would be amazing to see.

And I think that’s one thing that we can all do. Whether you’re in the league or not, you’re an athlete or not, we have some kind of power. Think about sharing that power with someone else who has less and what that could achieve.

DF: It’s odd to say, but I thought that the film couldn’t have come at a better time. We’ve had this national conversation about violence against women, sexual assault, and gender bias with the #metoo movement. Equal pay is a policy demand, a chant on the streets, and [heard] in U.S. Women’s National Team soccer games. And the last few years there have been multiple outlets like the Washington Post, the New York Times that’ve reported on the problems associated with NFL cheerleaders. And now your film will release today. So I’m just curious, did you have any expectations for the documentary when you started filming? And how did those expectations change over time?

YG: I think for me, in starting the film, obviously I knew right away that this was tackling a huge beloved [American] pastime. It’s a hugely popular institution. But it was definitely an uphill battle in 2014 when we were trying to pitch the film to funders, when we were just talking to people about the angle the film takes, which is the lens of gender inequality and labor when it comes to cheerleading.

I think there were a lot of the same stereotypes that the women face as we were trying to pitch the film.

My team and I were just focused on making something that really rang true for us. And that spoke to our experience as women, as women of color actually. ’Cause most of [my] team members were actually all Asian-American women. And we didn’t foresee that the #metoo movement would come about, which was amazing. And I think that kind support that women showed each other and the kind of bravery that women were exercising while sharing their stories, it was hugely inspirational. And it also, as you mentioned, led to a bunch of other women filing lawsuits or federal complaints or speaking out through huge outlets.

So I think that was a big shift and that in some ways made our film more fruitful, more interesting, because now we can have those conversations. I think some of the biggest areas we face, it was just like the lack of ability to even talk about some of these issues without feeling like they’re taboo or just like being dismissed or something. But now we definitely have more open minds and I think that is amazing.

At the same time, I do think there’s still a long way to go. I’d say there’s a lot of optimism, but I think there’s still the victim-blaming, misogyny, all of that is still there. But the more that we talk about it the more we can shine a light into those places that never saw the light of day.

DF: I wanted to ask a question about sports documentaries. And just before I ask this, would this technically be considered your first sports documentary or sports topic that you covered?

YG: Well, so back in 2014, I started another feature documentary that was finished earlier. I co-directed a film called Who Is Arthur Chu, which is about Jeopardy. I know people wouldn’t say Jeopardy is a sport. It’s a competition. There’s training, there’s tournaments and all of those things [so] there’s kind of similarly structured. I would say this is sort of more a direct foray into the world of sports documentary.

I am a huge fan of ESPN’s 30 for 30, I’m watching some of the [HBO’s] Real Sports and also the 24/7 episodes. I don’t even like watching boxing, but I like watching those shows and those documentaries cause it’s a window into the culture, and the people in the society and these individuals and the narratives that really come with that. So that’s why I like sports documentaries, and that’s why I hope that this film can help sort of expand the genre a little bit because I think sometimes sports documentaries can get stuck in this very similar kind of structure and narrative. I think there is room to innovate and also just, again, for audiences to have different angles and different approaches to looking at similar things.

DF: Yeah. I mean, you answered my question before I even asked it. I feel like now is such an amazing time for the sports documentary, but also, you know, there are some that I feel are honestly cheerleaders for the sports industry. Yours is definitely not one of those.

YG: I guess that’s what I’m interested in as a filmmaker, right? [It’s] these people that are rebels or in the margins, but are trying to take on this larger system or institution. They may not succeed, but then, they evolve as people. That to me is really interesting. I’m not interested in just making things that are kind of, like you said, fiercely loyal to some kind of industry. That’s not something that interests me as a filmmaker. I love watching them.

Like I thought The Last Dance was really fun to watch, but am I going to dedicate my time as a filmmaker to making something like that? No, not at this moment. I really need to find a hook there that is somehow like a misbehaving element or something for me to be interested in.

DF: Is there anything I missed that you would like to add for the record or like me to know or potential viewers of your film to know?

YG: I guess you kind of asked [earlier via email] about the future of NFL cheerleading and any efforts to unionize. I’m really proud that the film is part of a growing wave, a growing momentum, I would say, of women coming together to really make league-wide change.

I think this season, especially the season we’re in, has been so tumultuous. It has been so crazy. And I feel like it is a good time to have a reckoning. And I really hope that it will happen.

This conversation was edited for clarity.

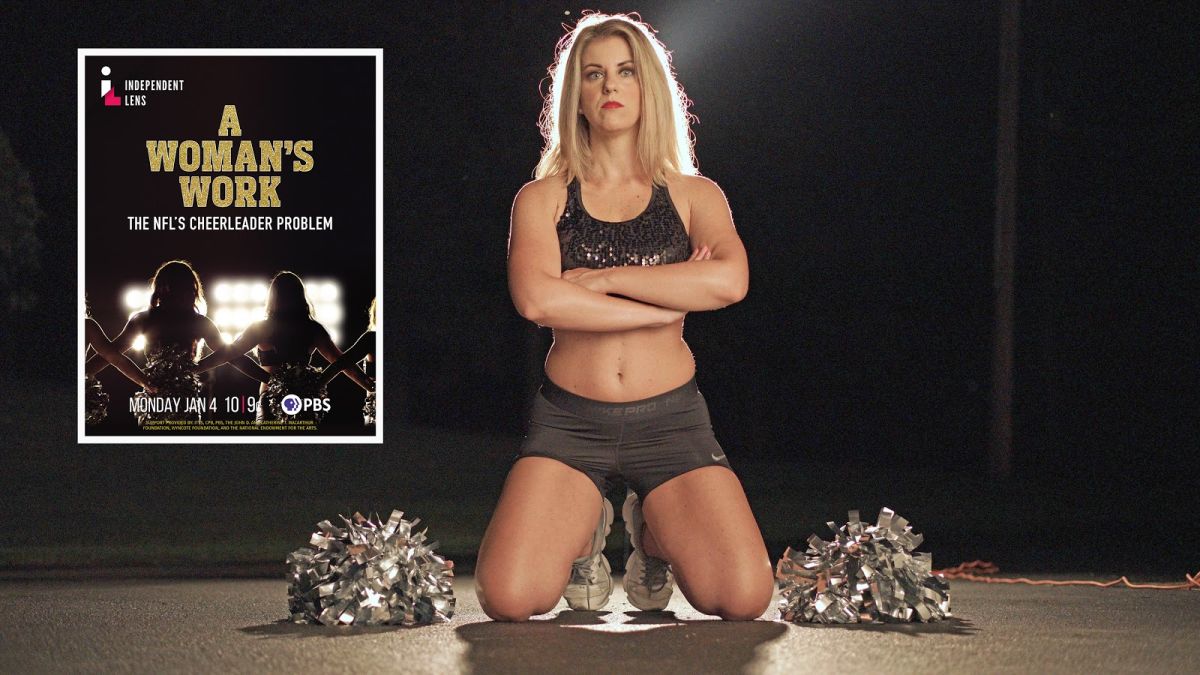

A Woman’s Work: The NFL’s Cheerleader Problem makes it broadcast premiere on Independent Lens on PBS on Monday, January 4, at 10pm ET check local listings.

This article is auto-generated by Algorithm Source: deadspin.com